Meteors: A Component of Space Weather

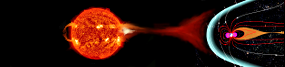

The usual concern of space weather is the varying electromagnetic energy and atomic particle flux throughout the interplanetary medium mainly from the Sun to the Earth.

However, larger particles traverse this region and influence our space environment in a number of ways. When these particles enter the Earth's atmosphere frictional forces heat the surface of the particle to high temperatures, creating light and atmospheric ionisation. We call this phenomenon a meteor and the particle that produces it a meteoroid. Both the meteor and the meteoroid contribute to space weather.

The meteor may be used to support communication at low VHF frequencies. This idea was explored in the 1950's and is now used for low cost data transmission. The data is transmitted in bursts following detection of a pilot carrier when a meteor occurs with the correct geometry. Such communication is suitable for remote areas, and because the path is very sensitive to the aspect geometry it allows for relatively secure or private data transmission. Meteor burst communication is also particularly suited to high latitudes and to very disturbed propagation environments (eg following detonation of nuclear explosives in the atmosphere).

Although meteors can enable a particular mode of communication, they may also cause interference to HF radio systems. In particular, Doppler HF radar can suffer jamming during times of intense meteor activity. The meteors reflect back the transmitted signal but spread it over a wide area of 'Doppler space'. Such interference makes it difficult to sort out the desired echoes due to aircraft or other targets.

The two effects discussed above, one constructive and one destructive, are both produced by the meteor ionisation. However, it is possible that the meteoroid itself may produce direct damage to a satellite. This was a large source of concern in the early days of space exploration, but the hazard turned out to be less severe than initially expected. However, this threat may increase dramatically during certain years. The Leonid meteor shower, which occurs around Nov 17 each year, increases a thousand fold every 33 years. In 1966 the normal hourly rate of around 5, shot up to 10,000!

The great Leonid storm of 1833 as shown on a woodcut

(from Meteors, by Neil Bone, published by Sky Publications)

Material prepared by John Kennewell